Alumni Spotlight: Libby Indermaur (`19) Serving a distinct population

Libby is a graduate student at Cornell in the Chris Smart Lab, School of Integrative Plant Science Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section. A teaching experience at a local prison has inspired Libby.

During the spring 2024 semester, doctoral student Libby Indermaur was a teaching assistant in Professor Emeritus Bill Fry’s plant pathology course at the Cayuga Correctional Facility in Moravia, New York. Through the Cornell Prison Education Program (CPEP), incarcerated individuals can earn an associate’s degree, and some students aspire to eventually earn their bachelor’s. The course inspired Indemaur, who is studying plant pathology, to pursue teaching as a career.

When Libby Indermaur entered NC State as a freshman studying horticulture, she never imagined where her journey would take her. A casual recommendation from a professor led her to a plant pathology class that sparked an unexpected passion, eventually guiding her to a Ph.D. program at Cornell. As she pursued her studies, Libby’s commitment to plant pathology grew, but she felt uncertain about teaching. Then, an opportunity came her way that would change her life—a chance to serve as a teaching assistant at the Cayuga Correctional Facility through the Cornell Prison Education Program (CPEP).

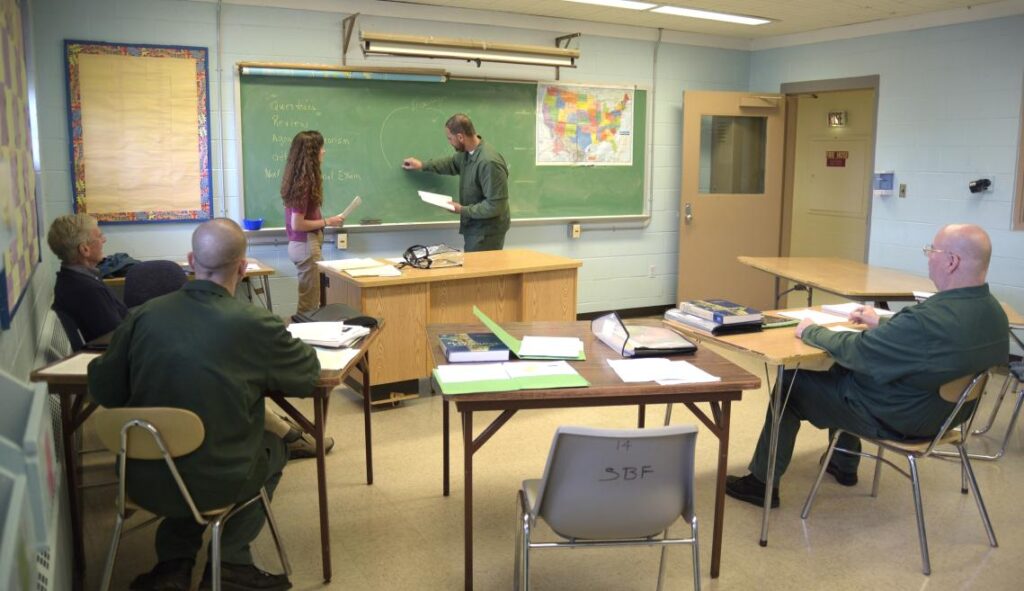

Libby’s time teaching plant pathology to incarcerated individuals transformed her view on education, service, and leadership. Stepping into this unconventional role at Cayuga Correctional was daunting at first. The prison was, as she described, “an intimidating place to volunteer.” She’d expected to teach with the typical tools of her discipline—microscopes, samples, PowerPoints, and videos—all essentials for teaching a hands-on subject like plant pathology. However, in the prison setting, such tools were out of reach. “We only had a chalkboard, printouts, articles, textbooks, and three hours once a week to teach the students about plant pathogens and their resulting diseases,” she recalls. Despite her initial anxiety about navigating these limitations, Libby found herself innovating and growing as a teacher in ways she hadn’t anticipated.

With physical resources restricted, she turned to the dynamics of the classroom itself to create an engaging learning environment. She and her co-instructor, Professor Bill Fry, set the classroom in a circle as much as possible, encouraging discussion and mutual respect among all participants. “We were always asking the students, ‘Who wants to explain this back to us?’” she says. Each time a student stepped up to the board to share what they’d learned, their peers would guide them, offering corrections and support. Libby found that these interactions helped everyone feel invested, making the learning process a shared journey.

One student’s story particularly moved her. He enrolled in the course not out of academic necessity but as a way to connect with his mother, a master gardener in Oklahoma. His goal was to learn enough to engage her in conversations about her passion. Inspired, he chose to study peach crops for his final project, as they were important to his mother. He even asked her to mail color photos of disease symptoms to help him complete his paper. “Both he and his mom were so invested in his success and in him contributing what he could to the class,” Libby recalls. This student’s dedication to his family, and the power of education to strengthen bonds despite difficult circumstances, left a lasting impression on her.

Through her experience at Cayuga, Libby was struck by how education could break down barriers and foster genuine connections. She describes how her preconceptions melted away, enabling her to view her students not merely as “incarcerated individuals” but as people with unique stories, motivations, and dreams. “I was shocked by how quickly I could forget we were in a prison,” she says, describing the classroom as a space where learning was valued and protected. Over the weeks, she came to know her students, men between the ages of 30 and 60, who were as eager as any Cornell student to learn, question, and grow. Her initial fears faded as she saw them engaged in the material and invested in one another’s success.

Teaching within CPEP reinforced a fundamental value that Libby has carried since her time at NC State: a commitment to servant leadership. She sees her path as part of a larger purpose, informed by NC State’s and Cornell’s shared mission as land-grant universities to serve communities beyond their campuses. This mission, which connects knowledge and leadership to community needs, gave her work a profound sense of meaning and relevance. “I am motivated to go into the class, the field, wherever the need presents to solve the problems of our stakeholders. NC State planted that in me,” she says. “Caldwell Fellows taught me to look at service from many viewpoints. It’s not simply volunteering on a Saturday to get volunteer hours, as I once thought. Rather, there is service in everything. There are populations that we do not see on campus but for whom we have an opportunity and responsibility to serve.”

When she attended her students’ graduation, Libby was moved in ways she didn’t expect. Watching them take off their caps and gowns to return to the constraints of prison life was a stark reminder of the challenges they still faced. “When I graduated, I moved on to the next thing. It shook me that they did not have that option despite having earned so much,” she reflects. The ceremony underscored the complexities of progress in the prison setting, as well as the power of education to give hope, agency, and a sense of purpose, even in the most difficult circumstances.

Libby’s time at Cayuga Correctional not only redefined her professional goals but also expanded her understanding of leadership and service. Inspired by her students’ resilience and dedication, she now knows that her future lies in teaching, helping others discover their potential, and carrying forward the mission to serve. Her story reminds us that true leadership is often found in the most unexpected places and that service can flourish in any environment, given the right commitment and care.

Kathleen Curtis originally wrote this story. It has been modified with additional content from a conversation between Dr. Odom and Libby. Parts of the original article have been reprinted here with permission from Erin Rodger, Senior Manager in the Office of Marketing and Communications at the Cornell College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

https://cals.cornell.edu/news/2024/08/student-inspired-teaching-experience-local-prison